Inventing a great product is pointless if nobody buys it. But many businesses in the R&D phase are so focused on development they put off serious thought of commercialization – only to discover too late the market for their product just isn’t there. Yes, they have a product, but they don’t have a business. To create a business you need to successfully commercialize the product.

In my years creating biomedical products and businesses, I’ve discovered there are three fundamental laws of commercialization that you need to consider early in the development process if you are to be successful.

Stuart’s First Law of Commercialization (with special thanks to Galileo and Newton):

An object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted on by an external force.

Newton was talking about the inertia of objects, but the rule also applies to people. Most people won’t change their behavior unless they are forced to. It’s human nature.

The phenomenon is so prevalent that behavioral economists have given it a name: status quo bias. What that means is, people prefer things to stay the same and reject change – even if it could lead to a better outcome for them. This helps explain everything from why people are slow to change utility or phone plans, to why people get stuck in bad habits like eating unhealthy food.

This resistance to change can have a huge impact on the success of a product. People tend to blame sluggish adoption on price or features or marketing, but often it is simply that their target market don’t want to change.

This is particularly true for pioneering products. Entrepreneurs often think that because their product is innovative, people will flock to it. But, in my experience, it’s actually the opposite. The more innovative the product, the bigger the force needed to enact change. Even if there is compelling evidence that your product is superior to current ways of doing things, many people will be hesitant to adopt it.

When someone tells me they have created a product that is so innovative it has no competitors, alarm bells immediately start ringing. As marketing folks will tell you, it’s easier to claim a slice of the market for a recognized product category, than to create a market for a new product category.

Not to say it’s impossible, it just requires a larger force to do it.

What sort of force am I talking about? In healthcare, it’s often regulatory reform or changes to reimbursement, but other external forces also have an impact.

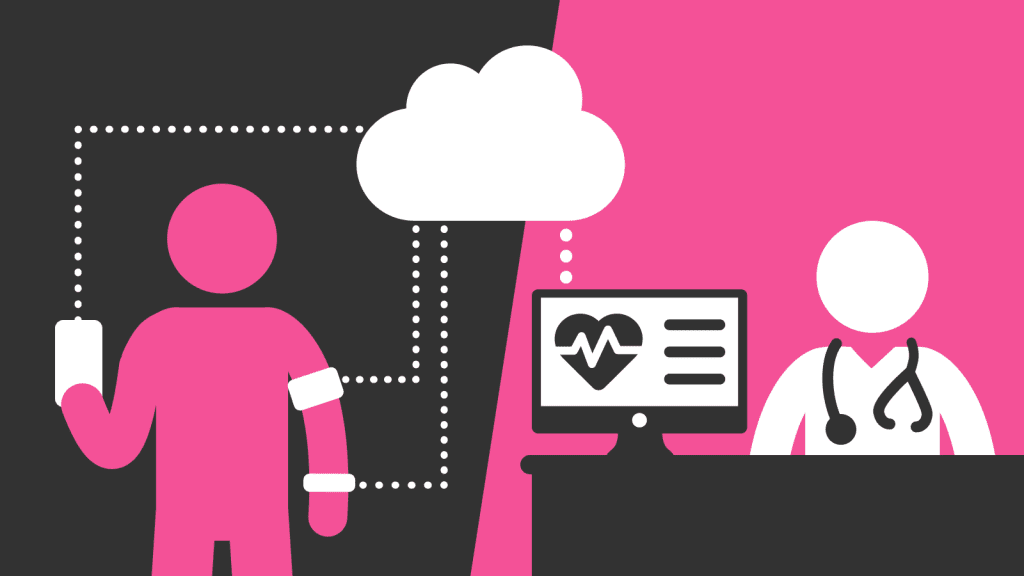

For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed how healthcare is delivered. As our GM of Digital, Kaushal Vyas, recently wrote, the pandemic is looking like the catalyst needed for widespread acceptance and adoption of digital health tech, such as remote patient monitoring, at least in the U.S. The technology has been available for years, but until the pandemic, clinicians, patients and healthcare organizations did not have the motivation needed to change the status quo.

So, how do you know if your product is the one that is going to cut through and actually be adopted?

In my experience, a good test is to give it away for free. If possible, give an early version or prototype of your product to your physician, or an aged care home, or your elderly parents, or whoever your mainstream target audience is, and see if they actually use it. I have often bought my elderly parents the latest aged care products, only to find I cannot convince them to use them. Even free products are hard to get adopted.

If you don’t have a usable product to give away, try buying the closest possible competitor product and see what the barriers to adoption are. If the customer genuinely says “I would use this if it had XYZ features”, and that matches your product vision, then you are on to a winner. But, if like my parents, the customer says something like “I just prefer to do things the way I always have” then no amount of R&D is going to change that.

I appeal to all budding entrepreneurs to heed this rule and never underestimate the force required to change behavior, especially if you have a game-changing product.

Stuart’s Second Law of Commercialization:

Clinical need ≠ Market Need

This law is critical for anyone working in the healthcare space. Just because there is a clinical need for something, does not mean there is a market need.

In other words, don’t think your product will sell just because it improves health outcomes. Even potentially life-saving products can fail commercially if there are not people or organizations with money to spend on the product.

Take, for example, rapid point-of-care flu testing. In the U.S., point-of-care flu tests are reimbursed. In Australia, they are not. The U.S. runs millions of point-of-care flu tests every year. Australia runs virtually none. The clinical need in both countries is the same; everyone gets the flu. But because Australia’s Medicare reimbursement rules favor lab testing (and we do have a very good lab system), there is literally zero market need. So, with the same product, you have a US$100 million+ market in the U.S., and a $0 market in Australia.

Or let’s look at smart hospital beds.

In the U.S., almost every hospital bed is set up with sensors to monitor a patient’s vital signs and raise an alarm if anything is wrong. When I spoke to nurses in the U.S. a few years ago for some voice-of-customer research, many of them had never even seen a ‘dumb’ hospital bed in their careers. But in Australia, outside of emergency, the most advanced thing most hospital beds can do is go up and down. Hospitals rely on nurses making regular checks on patients to make sure they are okay.

Now, there is no denying that smart beds are better than dumb beds. They provide constant patient monitoring and take the burden off nursing staff, potentially helping to make hospitals safer and more efficient. But they are a lot more expensive than regular hospital beds. And in Australia, without regulation to accelerate adoption, hospital administrators are choosing to spend their valuable resources elsewhere. This is not necessarily bad. There are lots of things that Australian hospitals do better than hospitals in America – partly because they are spending money differently and some may argue more productively. But when it comes to smart hospital beds, while the clinical need is there, the money, and thus the market, is not.

So if you’re working in the medical space, please don’t assume there is a market need because your product provides a better clinical outcome. Clinical need ≠ market need.

Stuart’s Third Law of Commercialization:

Market pull = Money

My third and final rule stems from a principle that PI has adopted since day 1, it is about market-led innovation. That is, to adopt a ‘market pull’ approach to product development, rather than ‘technology push’.

The best way to discover if there is market pull for your product early on is to go and find a partner that is willing to put up some money to invest in your partnership.

I don’t mean a vague commitment to buy your product in the future; those people are innovation window shoppers and can waste a lot of your time and never come onboard. I mean money upfront.

You need a partner that is so acutely aware of the unmet need and therefore so keen to see your product on the market that they want to help it get there (and they may want a good deal or a piece of the action in the process).

Partners come in many shapes and sizes. They could be a distributer like Henry Schein, a pharma company like Johnson & Johnson, a medtech company like Medtronic, a healthcare system like the NHS, or individual healthcare providers or insurers. What’s important is that you are strategically aligned, and they are willing to show that with $$.

If you can’t find a company that’s willing to put money down to progress your partnership, why do you think it will be any different when you’re actually trying to sell your product? No eager partners is a first warning sign that it may be difficult and expensive to find eager customers down the track.

Finding a partner confirms that there is indeed market pull for your product. Partnering also has two other huge benefits.

- You get money to continue your development and commercialization. If you don’t find a partner, you’ll need to fund it all yourself–which is hard—or you may need to get in bed with a venture capitalist—which often comes with strings attached that are misaligned with the interests of your business and founding shareholders.

- You get access to valuable market insight. Your partner is likely dealing with the problem you are solving day in, day out. Use their knowledge and experience to improve your innovation. This deep insight is like oxygen for a start-up; it is absolutely invaluable and could be the difference between success or failure.

Through PI, we’ve worked with several companies who have formed successful partnerships early in the development process. Genea Biomedx partnered with Merck to commercialize its innovative range of fertility technologies. Australian start-up Scinogy is collaborating with Thermo-Fisher Scientific to develop and commercialize instrumentation and reagent systems aimed at improving productivity and scalability of cell and gene therapy manufacturing. Another Aussie start-up, solar-sharing platform Allume, secured funding from real estate group Mirvac as well as a commitment to install Allume’s system in its new apartment complexes. These partnerships gave the companies the confidence they were on the right path as well as the security of a clear route to market.

Summary

If you’re embarking on a new product development, don’t stick your head in the R&D sand and hope for the best when it comes to commercialization. Obey my three laws and go out and test them. Try giving an early version of your product away for free, interrogate the market need not just the clinical need, and find a partner willing to invest in your product or business. That way you can continue on your product development journey confident that there is a market with customers willing and able to buy your product.